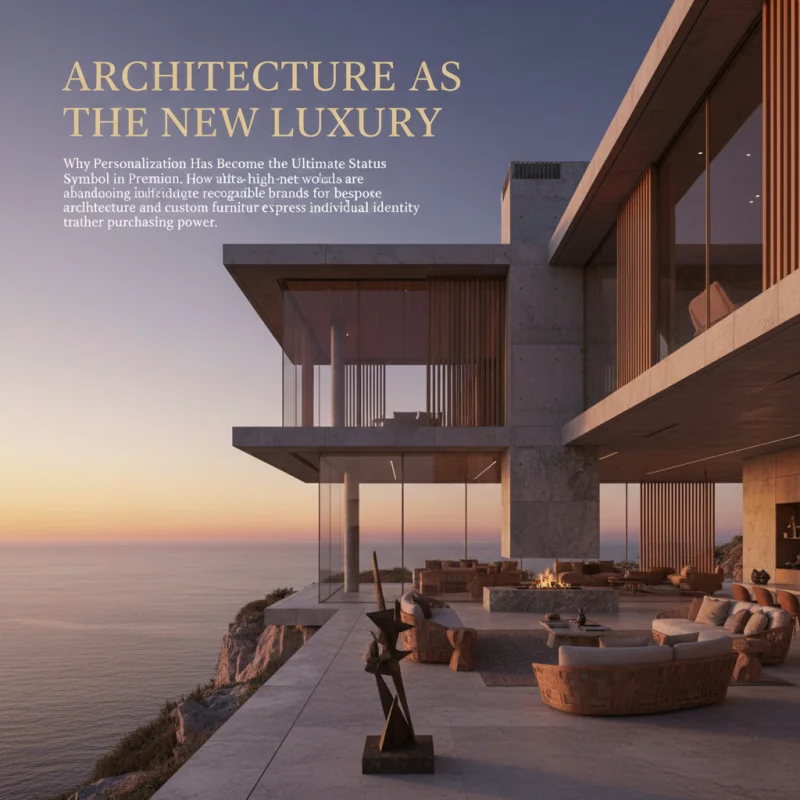

What happens when space itself becomes luxury—the unique challenges, extraordinary opportunities, and design philosophies that define truly expansive residential architecture

Published: December 2025 | Reading Time: ~13 minutes | Category: Ultra-Luxury Residential Design

The first time you walk through a residence exceeding 1,000 square meters—roughly 10,000 square feet—you experience something that fundamentally shifts your understanding of domestic architecture. Scale transforms everything. Rooms that would be generously sized in normal homes become merely adequate. Furniture that dominates typical living spaces appears almost diminutive. Design challenges that never arise in conventional residences become central concerns.

I experienced this viscerally during my first major commission for a grand estate—a 15,000 square foot villa in Bangalore’s Embassy Golf Links. As our team delivered custom furniture we’d spent six months creating, I watched pieces that had seemed monumental in our Tamil Nadu workshop find their places in rooms so vast they looked appropriately sized rather than oversized. A dining table extending sixteen feet—absurdly large in most contexts—sat comfortably in a dining room that could have accommodated something even grander.

That project taught me that designing for estates beyond 1,000 square meters isn’t simply doing more of what works in smaller spaces. It’s a fundamentally different discipline requiring different thinking, different skills, different understanding of how people actually inhabit expansive residences. The rules change. The proportions shift. What works brilliantly in a 3,000 square foot apartment fails completely in a 12,000 square foot villa.

Over the subsequent two decades, we’ve created custom furniture and interiors for dozens of grand estates across India and internationally—properties ranging from 1,000 to 5,000 square meters, from relatively modest (by these standards) family homes to palatial structures that rival small hotels in size and complexity. Through this work, we’ve developed understanding of what makes these properties succeed or fail, what transforms mere bigness into genuine grandeur.

The Paradox of Space: When More Becomes Different

The central challenge of grand estate design is a paradox that surprises clients commissioning their first truly large residence: more space doesn’t make design easier. It makes it exponentially harder.

In smaller residences, space constraints force discipline. You can’t include everything you want, so you make careful choices. Room sizes are limited, so furniture must be appropriately scaled. The physical limitations themselves guide design decisions.

Grand estates remove these constraints, and in doing so remove the structure that makes design decisions straightforward. When your great room can be thirty feet long or sixty feet long, when you can include four guest suites or ten, when every fantasy and whim could potentially be accommodated, the burden of choice becomes overwhelming.

We see this repeatedly with clients commissioning large estates. The excitement of “we can do anything” quickly becomes the paralysis of “how do we decide what to do?” The unlimited possibility that makes grand estates appealing also makes them extraordinarily difficult to design successfully.

The solution isn’t adding more features or filling every space. The solution is developing rigorous conceptual frameworks that bring coherence to vast square footage. Successful grand estates feel intentional and composed despite—or perhaps because of—their immense size. Failed grand estates feel like collections of rooms and features assembled without organizing principle, impressive in aggregate square footage but incoherent in experience.

Let me share what we’ve learned about creating that coherence, about transforming expansive space from overwhelming to extraordinary.

Establishing Spatial Hierarchy: The Architecture of Sequence

The first principle for grand estate design is creating clear spatial hierarchy—understanding that not all spaces are equal, that some rooms should feel more important than others, that the experience of moving through the residence should have rhythm and progression.

In smaller homes, hierarchy emerges almost automatically from functional organization. You enter through a foyer, proceed to public spaces, retreat to private areas. The sequence is compressed and obvious.

Grand estates require deliberate orchestration of spatial sequence. The journey from entry to the residence’s most significant spaces—whether a great room, a formal living area, or a spectacular view terrace—should be carefully choreographed, creating sense of anticipation and revelation.

We recently worked on a Delhi farmhouse spanning 2,200 square meters where this spatial hierarchy was initially missing. The architect’s plan showed entry directly into a massive living hall—forty feet by sixty feet with twenty-foot ceilings. Impressive, certainly, but the impact was immediate and complete. Once you’d seen that room, where else could the house go? How could anything else compete with that overwhelming first impression?

We worked with the clients and architect to introduce intermediary spaces—a reception gallery creating transition between entrance and great room, a secondary sitting area offering alternative to the overwhelming main space, circulation paths allowing movement through the house without constantly returning to the dominant central volume.

The revised sequence created rhythm: impressive entry hall, intimate reception gallery, dramatic great room reveal, comfortable family living area, serene private spaces. Rather than one overwhelming room dominating, the house offered journey of varying scales and moods, each space preparing you for the next.

The furniture we created supported this hierarchy. The great room received our most dramatic pieces—a sixteen-foot dining table in sustainably sourced rosewood, seating for twenty in custom sectional configurations, statement console tables and cabinets. The family living area got more intimate pieces—comfortable deep-seated sofas, modest coffee tables, cozy reading chairs. The scale and formality of furniture reinforced each space’s position in the overall hierarchy.

This spatial sequencing determines how grand estates are actually experienced. Guests remember not individual rooms but the journey through spaces, the rhythm of compression and release, intimate moments and grand gestures. Designing that experience requires thinking cinematically—understanding how people move, where they pause, what they see and when they see it.

The Problem of Proportion: When Normal Furniture Disappears

One of the most common failures in grand estate furnishing is bringing normal residential furniture into spaces that demand something more substantial. A sofa that looks generous in a typical living room appears diminutive in a room with eighteen-foot ceilings and forty-foot length.

This isn’t just aesthetic problem—it’s functional failure. Furniture that’s physically too small for the space can’t properly define or organize it. A seating arrangement that would comfortably anchor a normal living room gets lost in a vast great room, failing to create the sense of enclosure and intimacy that makes spaces usable.

We solve this through what we call “architectural furniture”—pieces designed with mass and presence sufficient to hold their own against grand architecture. This doesn’t mean simply making everything bigger. It means understanding the relationship between furniture scale, room volume, and human scale.

For a Mumbai estate with a living hall measuring forty-five feet by thirty-five feet with sixteen-foot ceilings, we created a seating arrangement totaling twenty-four linear feet—three large sectional sofas in L-configuration. In a normal living room, this would be absurdly oversized. In this space, it was exactly right, creating an intimate conversation area within the vast room.

But even within this grand seating arrangement, we maintained human scale in the details. Seat heights, depths, and back angles were designed for comfort, not monumentality. Arm heights allowed for comfortable resting. The cushions, while large in aggregate, were sized for human bodies.

This balance—furniture with architectural presence but human-scale detail—is crucial for grand estates. Spaces must feel impressive without feeling inhuman, grand without being intimidating.

The principle extends to all furniture categories. Dining tables for grand estates typically need to accommodate twelve to twenty guests, requiring lengths of fourteen to twenty feet. But the table height remains standard seventy-five centimeters, optimized for human dining comfort. Consoles and cabinets may be six or eight feet long, but their surface heights align with human reach and proportion.

We also use furniture to create scale transitions within large rooms. A vast living hall might include a substantial seating area for entertaining, but also a more intimate reading nook with smaller-scale furniture near a window. The variety helps people understand and relate to the space, providing options for different moods and group sizes.

Creating Intimacy in Vastness: The Paradox of Comfort

The greatest failure of many grand estates is creating spaces that, while impressive, feel uncomfortable for actual daily living. Rooms designed to impress guests prove too formal and intimidating for family use. Owners find themselves retreating to smaller secondary spaces, leaving the grand rooms functionally unused except for rare entertaining.

The challenge is creating spaces that can accommodate both intimate family moments and grand social occasions, that feel comfortable for two people having morning coffee and also appropriate for a party of fifty. This dual functionality requires sophisticated design thinking.

We address this through layering multiple scales of furniture and creating flexible zoning within larger spaces. A forty-foot living room might be divided conceptually into three areas: a formal seating area centered on a fireplace for entertaining, a casual family area with comfortable deep-seated furniture oriented toward media, and a reading nook by windows with intimate-scale chairs and lighting.

For a Gurgaon estate, we created what we called “rooms within rooms”—distinct furniture arrangements within the larger great room, each scaled for different activities and group sizes. A formal conversation area used our most refined furniture in sophisticated materials. A family media area employed comfortable, slightly oversized pieces in more casual upholstery. A game area near the bar featured flexible seating that could be rearranged easily.

Each zone had appropriate lighting—ambient lighting for the overall space, task lighting for specific areas, accent lighting highlighting artwork and architectural features. This lighting flexibility meant the space could feel intimate when only one zone was lit for family use, or grand and unified when fully illuminated for entertaining.

The furniture fabrics and finishes also contributed to comfort. While we used sophisticated materials throughout, we avoided anything too precious or delicate. The rosewood dining table received a finish that could withstand daily family use without showing every mark. Upholstery fabrics combined luxury appearance with practical durability.

This comfort-in-grandeur extends to temperature and acoustics. Large volumes can be difficult to heat and cool efficiently, and hard surfaces in vast spaces create acoustic challenges. We work with architects and engineers to ensure spaces are thermally comfortable and acoustically pleasant, understanding that no amount of beautiful furniture can compensate for rooms that are too cold, too hot, or too reverberant.

The Service Infrastructure: Invisible Complexity

Grand estates require complex service infrastructure that residents rarely see but that fundamentally enables the lifestyle these properties promise. Understanding and accommodating this infrastructure affects furniture design and placement in ways that aren’t immediately obvious.

A 2,000 square meter estate might employ five to ten full-time staff—housekeepers, chefs, drivers, gardeners, security personnel. These people need discrete spaces to work and rest, storage for equipment and supplies, circulation paths that don’t intersect with family and guest circulation.

This service infrastructure affects furniture design in subtle ways. Storage furniture must accommodate not just family belongings but also linens, serving pieces, and equipment for formal entertaining. Kitchen and pantry spaces require professional-grade organization systems. Staff quarters need furniture that’s comfortable and dignified but distinct from family spaces.

We recently completed furniture for a Bangalore estate with eight full-time staff. The service areas—staff dining, rest areas, laundry, storage—totaled nearly 400 square meters. We created furniture for these spaces with the same attention to quality as family areas, but with more utilitarian styling and extreme durability. The staff would use these pieces daily, intensively, and they needed to withstand that use gracefully.

The butler’s pantry—the serving and storage area between kitchen and dining room—received particularly careful attention. This space houses china, crystal, silver, and serving pieces for formal entertaining, plus all the equipment and supplies needed for food service. We created custom cabinetry providing organized storage for literally hundreds of items while maintaining sophisticated appearance appropriate to its visibility to family and guests.

Understanding service requirements also affects furniture placement in public spaces. Serving tables and consoles need to be positioned where staff can access them easily without intruding on guests. Seating arrangements must allow staff to circulate with drinks and appetizers. These functional considerations, invisible when done well, become obtrusive problems when ignored.

Material Selection for Scale: When Wood Choice Matters More

The materials used in grand estate furniture carry additional weight—both literally and figuratively—compared to furniture for typical residences. The visual impact of materials becomes more significant when pieces are larger and when they’re viewed from greater distances.

Wood grain patterns that provide pleasant detail in normal-scale furniture become crucial design elements in architectural-scale pieces. A sixteen-foot dining table showcases wood grain in ways impossible with smaller furniture. The grain pattern becomes major visual feature, requiring careful selection for aesthetic impact.

For these large pieces, we seek wood with dramatic but balanced grain—enough figure to create interest across the expanse of a large tabletop, but not so busy that it becomes chaotic. We might spend weeks selecting specific boards for a major table, examining dozens of options to find exactly the right combination of grain, color, and character.

The wood species itself matters more in grand estates because furniture will be viewed from various distances and angles. Woods need sufficient color and grain contrast to read clearly from across large rooms. Timid woods that look fine in intimate settings can disappear in vast spaces.

We often use rosewood and walnut for grand estate furniture because these species have the visual strength to hold up at scale. Their rich colors and distinctive grain patterns create presence even when viewed from thirty feet away. Lighter woods like maple or ash, beautiful in other contexts, often lack the visual impact these settings demand.

Stone and metal also take on different roles in grand estate furniture. We use marble and granite more liberally than in typical residential work, incorporating stone tops on consoles and dining tables. The permanence and visual weight of stone complements the architectural scale of the furniture.

Metal bases and accents—typically bronze or blackened steel—provide structural support and visual interest. A dining table with stone top might use a bronze base with sculptural qualities strong enough to balance the top’s visual weight. Console tables combine wood and metal to create dynamic contrasts that remain interesting across the large spaces where they’re placed.

The Question of Style: Modernism vs. Traditionalism in Grand Estates

An interesting pattern emerges in grand estate design: truly modern, minimalist aesthetics prove surprisingly difficult to sustain across vast square footage. The restraint and emptiness that creates serenity in smaller modern spaces can feel stark and unwelcoming at grand estate scale.

This doesn’t mean grand estates can’t be contemporary in style. But successful contemporary grand estates typically incorporate more warmth, material richness, and detail than equivalent smaller residences. The modernist discipline of “less is more” needs recalibration at this scale.

We’ve observed this in our furniture commissions. A Bangalore client initially wanted stark modernist interiors throughout their 1,800 square meter villa—white walls, minimal furniture, no ornamentation. As we worked through the furniture design, it became clear this approach would create spaces feeling empty and cold rather than serene and refined.

We gradually introduced more warmth and texture while maintaining contemporary forms. Wood tones moved from cool grays toward warmer browns. Upholstery incorporated textured fabrics rather than smooth leather. We added carved details to what had been plain surfaces—not traditional carving, but contemporary geometric patterns that created visual interest and rewarded close inspection.

The result remained contemporary and uncluttered but felt substantially warmer and more inviting than the original vision. The clients acknowledged that the pure minimalism they’d envisioned worked beautifully in design magazines but didn’t create spaces where they wanted to spend time.

This doesn’t mean traditional or classical styles automatically work better at grand scale. Ornate traditional design can become overwhelming across vast square footage, creating visual chaos rather than richness. The key is finding appropriate level of detail and ornament for the scale—enough to prevent emptiness, not so much as to create confusion.

Our approach typically lands somewhere between modernist restraint and traditional richness. We use classical proportions and traditional joinery techniques but with relatively clean-lined contemporary forms. We incorporate detail and ornament selectively, creating moments of visual richness that punctuate larger areas of calm.

Cost Realities: The Economics of Grand Estate Furnishing

Clients commissioning grand estates should understand that furniture costs don’t scale linearly with square footage. A residence twice as large doesn’t require twice the furniture budget—it typically requires three to four times as much.

This multiplication comes from several factors. First, the furniture itself must be more substantial and complex, requiring more material and labor per piece. A normal dining table might use ₹50,000 in materials and 200 hours of labor. A grand estate dining table could use ₹3 lakhs in materials and 600 hours of labor.

Second, grand estates require more furniture overall. Not just larger pieces, but more pieces—additional seating areas, more guest bedrooms requiring full furniture suites, larger dining capacity, extensive storage solutions.

Third, the quality expectations rise. Clients investing ₹15-20 crores in architecture and construction rightfully expect furniture of commensurate quality. This means using finest materials, most skilled artisans, most refined finishing processes.

For a well-furnished grand estate of 1,500 square meters, clients should budget ₹1.5 to 3 crores for custom furniture alone. For a 3,000 square meter property, ₹4 to 6 crores becomes realistic. These figures often surprise clients who haven’t previously commissioned furniture at this level, but they reflect the reality of creating pieces worthy of the architecture they inhabit.

The positive side is that this furniture represents genuine investment. Properly maintained, these pieces will last generations and often appreciate in value. They’re not expenses that depreciate—they’re assets that endure.

The Future: Where Grand Estate Design is Heading

Grand estate design is evolving in interesting directions driven by changing client expectations and broader cultural shifts.

Sustainability has become non-negotiable. Clients building 3,000 square meter residences increasingly feel obligated to do so responsibly—using sustainable materials, incorporating environmental systems, creating buildings designed to endure rather than be demolished after one generation. This affects everything from architectural systems to furniture material selection.

Flexibility is increasingly valued. Grand estates designed to accommodate only one specific lifestyle prove limiting. Clients want spaces that can adapt—guest suites that function as home offices, entertaining areas that convert to exhibition spaces, outdoor areas that serve multiple functions.

Technology integration continues advancing, but smartly rather than obviously. The goal is homes that respond intelligently to occupants’ needs without looking like technology showcases. This affects furniture design as we incorporate charging solutions, integrated lighting and audio, climate control that works with rather than against furniture placement.

Most fundamentally, grand estates are moving away from ostentatious display toward quieter luxury that emphasizes quality, craft, and timelessness over mere size and expense. The most successful new grand estates feel composed and refined rather than bombastic and excessive.

This evolution aligns perfectly with our approach at Crosby Project. We’ve never pursued ostentatious design. Our furniture has always emphasized material beauty, craftsmanship excellence, and timeless proportion over trendy drama. As grand estate design matures in this direction, our work feels increasingly relevant.

Creating furniture for grand estates remains among our most satisfying work—challenging technically, rewarding creatively, meaningful in terms of creating pieces that will be treasured across generations. These aren’t just large furniture commissions. They’re opportunities to create at the highest level of our craft, working with extraordinary materials, unlimited time, and clients who appreciate true excellence.

This is what luxury should be—not wasteful excess but considered excellence, not temporary fashion but enduring quality, not mere display but genuine substance. This is what we strive to create in every grand estate we furnish.

For consultations on furnishing grand estates and luxury residences:

Tamil Nadu Workshop

355/357, Bhavani Main Road, Sunnambu Odai, B.P.Agraharam, Erode, Tamil Nadu 638005, India

Ireland Office

16 Leopardstown Abbey, Carrikmines, Dublin 18 D18YW10, Ireland

Contact: +91-8826860000 | +91-8056755133 | care@crosby.co.in