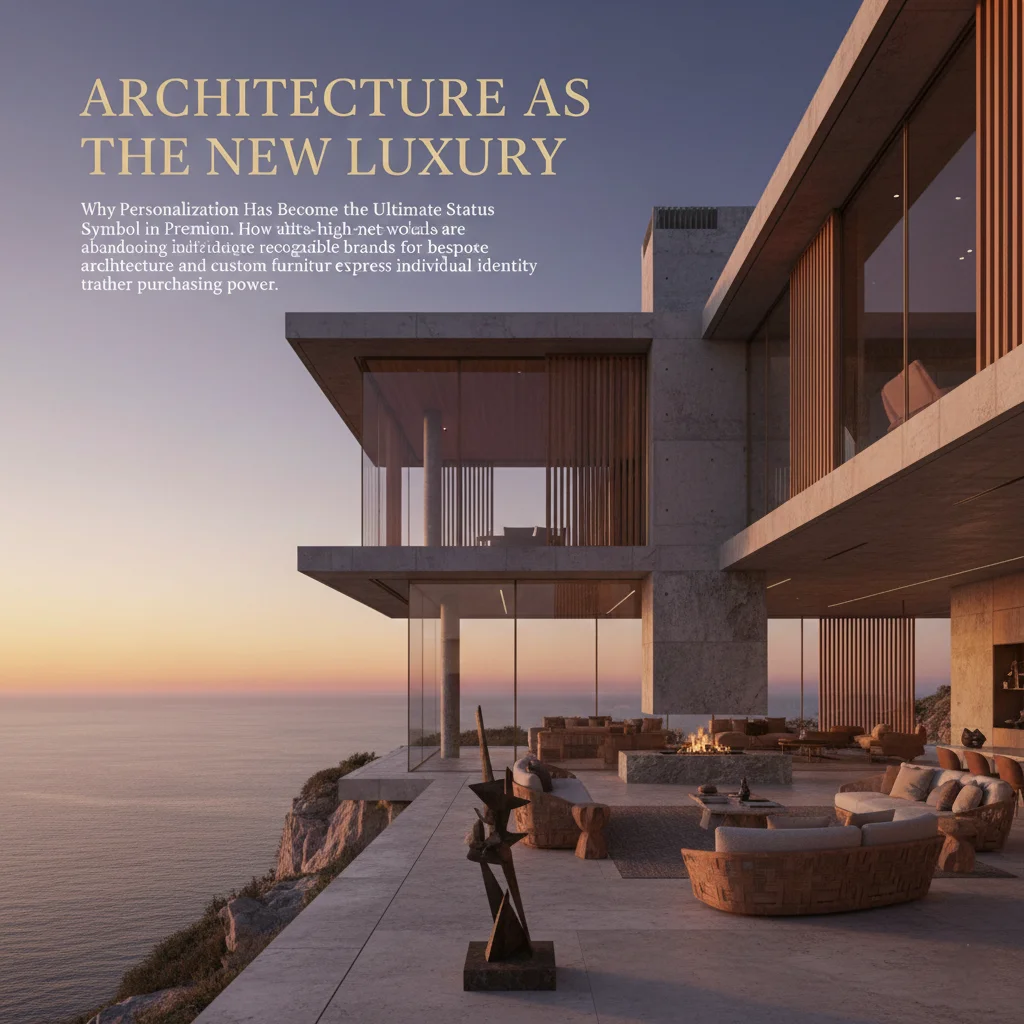

How ultra-high-net-worth individuals are abandoning recognizable brands for bespoke architecture and custom furniture that express individual identity rather than purchasing power

Published: December 2025 | Reading Time: ~14 minutes | Category: Luxury Design Philosophy & Cultural Trends

The meeting started with what seemed like a straightforward commission. A tech entrepreneur who had recently exited his company for a nine-figure sum wanted to furnish his new penthouse in Mumbai’s Worli—4,500 square feet with panoramic Arabian Sea views. He had the budget for literally anything, and I expected him to request furniture from the usual luxury suspects—Italian design houses, established European manufacturers, perhaps some iconic mid-century pieces.

Instead, he said something I’ve heard with increasing frequency over the past five years: “I don’t want anything anyone else can buy. I don’t want to walk into someone else’s home and see the same coffee table I have. I want furniture that exists only for me, that tells my story, that nobody else in the world possesses.”

He went on to explain his philosophy. For years, he’d pursued traditional luxury—the watch brands everyone recognizes, the car marques that signal wealth, the fashion labels that communicate status through logos. But at a certain level of wealth, he’d realized, everyone can buy those things. A $200,000 watch or a $300,000 car simply means you have $200,000 or $300,000. It doesn’t express anything about you as an individual.

What he wanted now was luxury that couldn’t be purchased with money alone—that required time, thought, collaboration with skilled artisans, deep personal involvement in the creative process. He wanted furniture that would make visitors ask “where did you get that?” and the answer would be “I had it made specifically for this space, for my life, by craftspeople in Tamil Nadu who spent six months creating it.”

This conversation encapsulates a profound shift occurring in luxury markets globally. For the first time in modern history, the most sophisticated and wealthy consumers are turning away from mass luxury—even very expensive mass luxury—toward radically personalized, bespoke, often unique objects and experiences. And nowhere is this shift more visible than in architecture and interior design, where the new luxury is absolute personalization.

The Death of Logo Luxury

To understand where luxury is heading, we need to understand what’s dying—what we might call “logo luxury” or “brand luxury.” This is luxury defined primarily by recognizable brands, by objects that signal wealth and taste through their association with established houses.

For most of the twentieth century and the early twenty-first, this model dominated luxury markets. You demonstrated sophistication by selecting the right brands—Hermès bags, Patek Philippe watches, Bang & Olufsen audio, B&B Italia furniture. The value derived partly from the objects’ quality but largely from the cultural capital associated with these brands. Other sophisticated people would recognize and appreciate your choices.

This model worked when luxury consumption was relatively exclusive, when only a small percentage of the global population could access premium brands. But two dynamics have fundamentally undermined it.

First, the democratization of luxury has made traditional luxury brands accessible to vastly larger populations. What was once genuinely exclusive—available only to perhaps one percent of the population—is now available to the top ten or even twenty percent in major global cities. When you see dozens of people carrying the same designer bag in a single afternoon in Mumbai or Dubai, the exclusivity that justified the premium has evaporated.

Second, and more subtly, the most sophisticated luxury consumers have developed what we might call “brand fatigue.” They’ve recognized that purchasing recognizable luxury brands isn’t really an expression of personal taste—it’s an expression of the ability to purchase recognizable luxury brands. The choice itself is delegated to the brand rather than made by the individual.

A client in Bangalore articulated this perfectly: “When I buy a Ferrari, I’m not expressing my taste in automobiles. I’m expressing that I can afford a Ferrari. The design choices, the engineering decisions, the aesthetic direction—none of that is mine. I’m just buying what someone else created.”

This realization has driven the most discerning luxury consumers toward bespoke everything—not just furniture and architecture, but clothing made by personal tailors, cars with custom coachwork, watches assembled to individual specifications, even custom fragrances blended specifically for individual clients.

The shift represents luxury’s evolution from consumption to creation, from selection to commission, from purchasing to patronage.

The Rise of Bespoke as Supreme Luxury

In this new luxury paradigm, the ultimate status symbol isn’t owning expensive things—it’s commissioning unique things. The process of creation becomes as important as the final object, and the story of how something came to be matters as much as what it is.

We see this daily in our Tamil Nadu workshop. Clients increasingly want to be involved in every stage of furniture creation. They visit our facility to select specific wood slabs for their dining table, examining dozens of options to find exactly the right grain pattern. They review design iterations, requesting subtle modifications until proportions feel exactly right. They meet with master craftsmen, discussing joinery techniques and finishing approaches.

This involvement transforms the transaction from commercial purchase into something closer to artistic patronage. Clients aren’t buying furniture—they’re commissioning it, participating in its creation, telling future guests “I worked with artisans in Tamil Nadu for eight months to create this table from sustainably harvested rosewood, using traditional joinery techniques passed down through generations.”

The story becomes inseparable from the object. The table isn’t just beautiful furniture—it’s narrative of personal taste, cultural engagement, commitment to craft and sustainability, patience to spend months on a single piece. These stories signal sophistication far more effectively than brand names ever could.

This shift toward bespoke extends across luxury categories. In fashion, the most sophisticated clients increasingly work with couture ateliers or bespoke tailors rather than buying ready-to-wear, even very expensive ready-to-wear. In automobiles, ultra-luxury manufacturers like Rolls-Royce now generate substantial revenue from bespoke customization programs where clients specify everything from paint colors mixed specifically for their cars to completely custom interior configurations.

In residential design, the trend reaches its fullest expression. A commissioned home represents the ultimate bespoke luxury—architecture designed for specific site and specific client, interiors created for particular lifestyle, furniture built for exact spaces and uses. Every element expresses the client’s individual preferences, values, and vision.

The contrast with luxury real estate of previous generations is stark. Wealthy individuals once competed to buy properties in the same prestigious buildings or neighborhoods, accepting whatever design came with the address. Today’s ultra-wealthy are more likely to commission architects to create unique residences on custom sites, treating the entire property as bespoke creation rather than commodity purchase.

Personalization as Cultural Capital

Why has personalization become the new status symbol? The answer lies in understanding how cultural capital—the prestige and recognition associated with taste and sophistication—now functions in globalized, digitally connected luxury markets.

In earlier eras, cultural capital derived from knowing which established brands represented quality and taste, from being able to distinguish authentic luxury from pretenders. This knowledge was relatively rare, requiring exposure to luxury culture that most people lacked. Demonstrating this knowledge through appropriate brand selection signaled membership in sophisticated circles.

But in the digital age, luxury brand knowledge has become democratized. Anyone can research which watch brands serious collectors favor, which furniture designers represent good taste, which fashion houses merit consideration. The information barrier that once created cultural capital has dissolved.

The new cultural capital derives not from knowledge of established luxury but from ability to commission bespoke luxury—from having the taste to envision what you want, the knowledge to select appropriate collaborators, the confidence to trust your own aesthetic judgment over established brands, and the patience to oversee complex creative processes.

This new cultural capital is genuinely rare. Most people, regardless of wealth, find the prospect of commissioning custom architecture or furniture intimidating. What if your taste is wrong? What if the final result doesn’t work? Isn’t it safer to select from established offerings that have been vetted by recognized tastemakers?

The willingness to commission bespoke luxury despite these uncertainties signals genuine confidence and sophistication. It demonstrates that you trust your own aesthetic judgment, that you have the cultural knowledge to collaborate effectively with architects and craftspeople, that you value uniqueness more than the safety of established brands.

This dynamic explains why bespoke commissions often get featured in design publications, shared on social media, and become conversation topics in sophisticated circles. They represent genuine expressions of individual taste rather than merely skillful brand selection. They tell more interesting stories and reveal more about their owners.

A dining table we created for a Delhi client—combining Indian rosewood with brass inlay incorporating patterns from her family’s ancestral property—has been photographed for multiple publications. The interest isn’t just in the table’s beauty (though it is beautiful) but in the story: how she conceptualized the design, how we translated her vision into reality, how traditional Indian craft techniques were employed to create something contemporary and personal.

That story creates cultural capital in ways that purchasing even the most expensive mass-produced dining table never could.

The Economics of Bespoke: Why Personalization Commands Premium

The shift toward bespoke luxury has interesting economic implications. Commissioned, personalized objects command substantial premiums over mass-produced equivalents, even very high-end mass production. Understanding why clients willingly pay these premiums reveals how luxury value is created in contemporary markets.

The most obvious value component is exclusivity. A custom piece exists in only one example. You can be certain no one else possesses an identical object. In an era when even expensive luxury goods are mass-produced in quantities of thousands or tens of thousands, true uniqueness carries substantial value.

But exclusivity alone doesn’t justify the premiums bespoke luxury commands. The deeper value comes from several additional factors:

Perfect fit and appropriateness: Bespoke objects are designed for their specific context—particular rooms, particular uses, particular aesthetic environments. A custom dining table is exactly the right size for its room, exactly the right height for its chairs, exactly the right style for its setting. This perfect appropriateness creates functional and aesthetic value impossible with objects designed for generic contexts.

We recently created a media console for a Bangalore client that illustrates this perfectly. The space was challenging—a wall with asymmetric architecture, specific equipment to accommodate, exact dimensions that didn’t match any standard furniture sizes. We designed a piece that responded to every constraint and opportunity, creating something that looked like it had always belonged in that space. A mass-produced alternative would have been compromise at best, awkward failure at worst.

Material quality and selection: Bespoke commissions allow selecting materials with care impossible in mass production. We spend weeks selecting specific wood slabs for major pieces, examining grain patterns, color variation, character. We can use genuinely exceptional materials—rare wood species, premium stone, aged brass—that would be uneconomical for mass production.

The dining table for that Mumbai tech entrepreneur I mentioned earlier used a single slab of Indian rosewood selected from dozens of possibilities. We chose this specific slab for grain pattern that created visual movement across the table’s length, for color gradation from warm honey at one end to deeper chocolate at the other, for small knot creating focal point near the table’s center. That level of material selectivity is possible only in bespoke work.

Craftsmanship excellence: Bespoke furniture can employ construction techniques and detail execution that would be prohibitively expensive in mass production. We use traditional hand-cut joinery that takes days per piece but creates joints strengthening over decades. We apply finishing techniques requiring weeks of patient work building up layers of finish. We incorporate hand-carving, inlay, and decorative details that would be economically impossible for mass production.

This craftsmanship creates both functional value—furniture that lasts generations rather than decades—and aesthetic value in details rewarding close inspection. Clients regularly report that they discover new aspects of pieces we’ve created years after installation, subtle details and refinements that reveal themselves gradually.

Emotional and narrative value: Perhaps most importantly, bespoke objects carry emotional and narrative value derived from the commissioning process itself. The memories of selecting wood, discussing design, meeting craftspeople, watching the piece take form—these become part of the object’s value. The story of its creation becomes inseparable from the object itself.

This narrative value proves remarkably durable. We’ve had clients tell us that specific pieces we created are designated in their wills for particular children, with the provenance documentation and creation story to be passed down along with the furniture itself. The objects have become family heirlooms not because of age but because of the meaning invested through the commissioning process.

The Design Process: How Bespoke Actually Works

For those unfamiliar with commissioning bespoke furniture or architecture, the process can seem mysterious or intimidating. Understanding how it actually works demystifies it and reveals why sophisticated clients find the process rewarding rather than burdensome.

Our typical furniture commission process includes seven stages:

Initial consultation and vision development: We meet with clients to understand their aesthetic preferences, functional requirements, and broader vision. This might involve reviewing images of furniture they admire, visiting completed projects to see our work in context, discussing their lifestyle and how spaces will be used. The goal is understanding not just what they want but why they want it.

Conceptual design development: Based on the consultation, we develop initial design concepts—sketches, 3D renderings, material samples. This gives clients something concrete to react to, refining their vision through response to specific proposals. We typically present multiple directions, allowing clients to select the approach that resonates most strongly.

Design refinement and iteration: Clients rarely love the first design iteration, and we don’t expect them to. We refine based on their feedback—adjusting proportions, trying different material combinations, modifying details. This iterative process continues until clients feel genuinely excited about the design. For complex pieces, we might go through six or eight iterations before finalizing.

Material selection: Once the design is finalized, we select specific materials. For wood furniture, this often means clients visiting our Tamil Nadu workshop to examine actual slabs. We show them options, explain how different choices will affect appearance and performance, help them understand tradeoffs between different possibilities. The final selection balances aesthetic preferences with practical considerations.

Fabrication and involvement: During fabrication, which might take three to six months for complex pieces, we maintain regular communication. Clients receive progress photos showing the piece taking shape. For local clients, we often invite workshop visits to see work in progress. This transparency builds confidence and allows course correction if needed.

Installation and placement: When the piece is complete, our team personally delivers and installs it. This isn’t just delivery—it’s careful placement ensuring the piece looks perfect in its intended location. We often make final adjustments on site, ensuring everything works exactly as intended.

Long-term relationship: Our relationship with clients doesn’t end at installation. We provide detailed care instructions and remain available for refinishing, repair, or future commissions. Many clients commission additional pieces over years, building complete collections of our work.

This process requires patience—three to eight months from initial meeting to final installation is typical for significant furniture commissions. But clients who’ve experienced it rarely find this timeline problematic. They appreciate that creating something genuinely special requires time, and they value being involved rather than simply waiting for delivery.

The architectural process follows similar patterns but at larger scale and longer timeline. Initial programming and conceptual design might take months. Design development and refinement can extend a year or more. Construction of a custom residence might require two to three years. The entire process from first meeting to move-in could span three to five years.

This extended timeline is feature rather than bug for sophisticated clients. They understand that creating unique architecture tailored to their specific needs and vision requires this patience. The process itself becomes significant life experience, and the result justifies the investment of time.

The Indian Context: Tradition Meets Personalization

The trend toward bespoke personalization takes distinctive form in Indian luxury markets, shaped by cultural traditions that have always valued custom creation over mass production.

Traditional Indian luxury—whether jewelry, textiles, or furniture—was almost always bespoke. Wealthy families commissioned pieces from specific craftspeople, often maintaining relationships with particular workshops across generations. Ready-made luxury in the Western sense didn’t really exist. Even relatively modest families would commission furniture from local carpenters rather than purchasing pre-made pieces.

This tradition of custom creation was disrupted during the twentieth century as Western consumption models penetrated Indian markets. Purchasing branded luxury goods became aspirational, signaling modernity and cosmopolitan sophistication. Traditional bespoke craft came to seem old-fashioned, associated with previous generations rather than contemporary luxury.

But the past decade has seen remarkable revival of appreciation for Indian bespoke craft, particularly among younger wealthy Indians who are confident enough in their cultural identity to value traditional approaches rather than viewing them as backward.

This revival takes contemporary forms rather than simply reproducing historical styles. Clients commission furniture using traditional Indian joinery techniques but with modern minimalist forms. They incorporate traditional craft elements—carving, inlay, traditional finishing techniques—but in restrained, contemporary applications.

Our work exemplifies this synthesis. We employ traditional Indian furniture-making techniques perfected in our Tamil Nadu workshop over generations. But we apply these techniques to contemporary designs that wouldn’t look out of place in Milan or New York. The result is furniture that’s distinctly Indian in its craft DNA but globally contemporary in its aesthetic.

This ability to synthesize traditional craft with contemporary design gives Indian bespoke luxury distinctive character. It’s not merely copying Western luxury or preserving historical Indian forms—it’s creating something new that draws strength from both traditions.

The synthesis resonates particularly strongly with successful Indian professionals who’ve lived internationally but maintain strong cultural connections. They want luxury that reflects their hybrid identity—globally sophisticated but culturally rooted, contemporary but connected to tradition, individual but authentically Indian.

A Mumbai client who’d spent twenty years in New York before returning to India articulated this perfectly: “I don’t want to pretend I’m European by filling my home with Italian furniture. But I also don’t want to live in a museum of traditional Indian design. I want furniture that’s as sophisticated and contemporary as anything from Europe but that’s clearly Indian in its craft and soul.”

The Sustainability Dimension

The shift toward bespoke personalization has unexpected sustainability benefits that increasingly matter to sophisticated luxury consumers.

Mass-produced furniture, even expensive mass-produced furniture, is designed for relatively short lifespans—typically twenty to thirty years before requiring replacement. The economics of mass production favor creating pieces that will eventually need replacement, generating ongoing revenue streams.

Bespoke furniture, particularly when created using traditional craft techniques and quality materials, can last indefinitely. Pieces we created twenty or thirty years ago remain in active use, looking beautiful and functioning perfectly. The longevity comes from construction quality—traditional joinery that can be tightened or repaired, solid wood that can be refinished rather than veneers that can’t, timeless design that doesn’t date.

This durability creates significant environmental advantage. Creating one piece of furniture that lasts a century consumes far fewer resources than creating three or four pieces that each last twenty-five years. The carbon footprint, resource consumption, and waste generation are dramatically lower for durable bespoke furniture.

Sophisticated clients increasingly understand and value this sustainability. They recognize that commissioning quality bespoke furniture represents more responsible consumption than purchasing mass-produced alternatives requiring eventual replacement.

The sustainability extends to supporting traditional craft economies. When clients commission furniture from our workshop, they’re supporting fifty-plus artisan families in Tamil Nadu. They’re ensuring traditional skills pass to younger generations. They’re preserving cultural knowledge that might otherwise disappear.

This support for craft communities and traditional skills appeals to luxury consumers who want their consumption to create positive impact rather than merely extracting value from supply chains.

The Future: Where Bespoke Luxury is Heading

The trend toward personalization and bespoke luxury shows no signs of plateauing. If anything, it’s accelerating as more luxury consumers discover the satisfaction of commissioning unique pieces and as the mechanisms for doing so become more accessible.

Technology is making bespoke luxury more achievable for broader populations. Digital design tools allow clients to visualize proposed pieces in their spaces before commissioning. Virtual reality can let them experience architectural designs before construction. Documentation and provenance tracking through blockchain can verify authenticity and craftsmanship.

But technology is enhancing rather than replacing human craft. The most successful luxury brands going forward will be those that synthesize digital tools with traditional skills—using technology to facilitate design and communication while relying on human expertise for actual creation.

We’re also seeing emergence of new hybrid models between mass production and pure bespoke. Some manufacturers offer extensive customization within structured frameworks—selecting from options for dimensions, materials, finishes, details. This provides many benefits of bespoke at lower cost and faster timeline than pure custom work.

But for the top tier of luxury consumers—those who can afford pure bespoke and who value absolute uniqueness—the future points toward even more personalization, even more involvement in creative processes, even more emphasis on craft, story, and individual expression.

The ultimate luxury is no longer owning the same expensive things as other wealthy people. The ultimate luxury is commissioning unique things that express your individual identity, that tell your story, that exist nowhere else in the world. This is where luxury has gone, and where it will remain.

For consultations on bespoke furniture and personalized interior design:

Tamil Nadu Workshop

355/357, Bhavani Main Road, Sunnambu Odai, B.P.Agraharam, Erode, Tamil Nadu 638005, India

Ireland Office

16 Leopardstown Abbey, Carrikmines, Dublin 18 D18YW10, Ireland

Contact: +91-8826860000 | +91-8056755133 | care@crosby.co.in